The

problem of evil as expressed by Aquinas

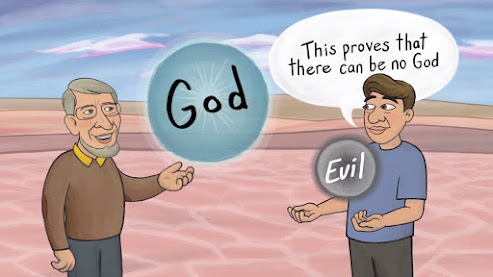

At Summa Theologica 1.2.3, Aquinas argues for the existence of God. He gives five proofs for the existence of God. Before doing so, he presents two objections. The first is from evil.

Obj. 1: It seems that God does not exist; because if one of two contraries be infinite, the other would be altogether destroyed. But the word God means that He is infinite goodness. If, therefore, God existed, there would be no evil discoverable; but there is evil in the world. Therefore God does not exist.

Today, we’ll focus on this

first objection, next week, the second.

The problem of evil has taken two forms…

These are the logical problem and the

evidential problem.

First, the logical problem

Some have argued that God

and evil cannot coexist (i.e., that these are incompatible). This is the problem of evil as expressed in Aquinas and by Mackie.

J. L. Mackie ‘Evil and

Omnipotence’

Theism is self-contradictory.

God and evil are incompatible.

Mackie begins with three essential claims of theism…

1. God is all good.

2. God is all powerful.

3. Evil exists.

To these, he adds two

claims of his own…

4. A good thing eliminates evil as far as it can.

5. There are no limits to what an all powerful thing can do.

It follows from the above

that one of the three claims of theism is false.

6. Therefore, one of (1), (2), and (3) is false

(Techincally, this is an argument not against the existence of God, but against theism, which Mackie supposes holds not only that God exists but also that evil exists.)

Evaluating the argument

Are premises (4) and (5)

true?

Does a good thing eliminate evil as far as it can?

Are there limits to what an

all powerful thing can do?

(1), (2), and (3) are

likewise controversial.

Classical theists such as

Aquinas view God’s goodness and power as something very different than ours. (We’ll

discuss this in two weeks when we take up God’s nature). Moreover, they deny

that evil is an exiting thing. (We’ll discuss this later today). Mackie’s

argument appears to have as its target a variety of theism that is often associated

with Protestantism.

Does a good thing eliminate

evil as far as it can?

(All that is needed is to

cast reasonable doubt on this idea.)

Means-ends responses

It’s worth noting that Mackie

must be speaking of a morally good agent… The idea is that such a one would try

to eliminate all of the evil he can.

Some deny that a morally good

agent would always do this.

A loving parent might not do

this. Might God be like this?

Aquinas’s means-end

response

Aquinas’s adopts a means

end response (together with other considerations).

Reply Obj. 1: As Augustine says: Since God is the highest good, He would not allow any evil to exist in His works, unless His omnipotence and goodness were such as to bring good even out of evil. This is part of the infinite goodness of God, that He should allow evil to exist, and out of it produce good.

The free will response

The idea is as follows…

1. It is good (or better) that people have free choice.

2. An all powerful God cannot ensure that people with free choice will always choose to do what is right.

3. Evil might result from their free choices.

4. This, evil is compatible with an all good, all powerful God.

Mackie rejects (2).

God could have created a different world in

which all choose rightly.

If there is no logical impossibility in a man’s freely choosing the good on one, or several occasions, there cannot be a logical impossibility in his freely choosing the good on every occasion. God was not, then, faced with a choice between making innocent automata and making beings who, in acting freely, would sometimes go wrong: there was open to him the obviously better possibility of making beings who would act freely but always go right. Clearly, his failure to avail himself of this possibility is inconsistent with his being both omnipotent and wholly good.

Mackie imagines that a scenario in which God’s

knows what everyone’s choices will be in various possible worlds and chooses

one in which the choices are always the right ones.

Some object that this would involve coercion.

I don’t think so.

Classical theists such as Aquinas do not see

God in this way. God knows our choices, they say, by causing them. Moreover, if

his causing of our world were to depend on the choices we would make in it,

this would appear to violate the doctrine of Divine impassibility.

Are there limits to what an

all powerful thing could do?

Turning to Mackie’s second

claim… Are there limits to what an all powerful thing can do?

Could God create a stone that he could not lift?

This silly question has

some important payoff. An all powerful being cannot create a contradiction… a

square circle or stone he can’t lift.

This is not really a

limitation because these aren’t things.

Perhaps one such thing is a

world in which there are free people who cannot choose wrongly… or a world in

which there are free people in which nothing bad happens. Some think that

natural evil is necessary for free choice to exist in a meaningful way.

The evidential argument from evil

Proponents of the problem of evil have

fallen back to another argument. The idea is that there is too much evil

in the world to be absorbed by be the free will defense and other such responses.

William Rowe’s evidential problem of evil

1. There exist instances of intense suffering which an omnipotent, omniscient being could have prevented without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse.

2. An omniscient, wholly good being would prevent the occurrence of any intense suffering it could, unless it could not do so without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse.

3. There does not exist an omnipotent, omniscient, wholly good being.

(The argument identifies evil

with suffering, i.e., what we don’t like.)

William Rowe's conclusion, to be precise, is that there probably

is no God. The apparently unabsorbed evils in the world count against the claim that God exists.

Rowe thinks it likely that

all evils are absorbed.

The "We don’t have the whole picture" response

One response to the evidential argument is to say that we do not have the whole picture.

Our understanding is

limited. The fact that we cannot see how something might contribute to the

goodness of the world does not give reason to believe that it does not.

The "Evil is a privation" response

Another is to deny that

evil is a positive property.

According to classical theists,

evil does not exist. Rather, it is a privation of good—a lack of something that

ought to be there. What God creates is good, Evil is not something that God

creates and so the fact of it is not incompatible with the existence of God.

Augustine thought this

For what is that which we call evil but the absence of good? In the bodies of animals, disease and wounds mean nothing but the absence of health; for when a cure is effected, that does not mean that the evils which were present — namely, the diseases and wounds — go away from the body and dwell elsewhere: they altogether cease to exist; for the wound or disease is not a substance, but a defect in the fleshly substance... Just in the same way, what are called vices in the soul are nothing but privations of natural good. And when they are cured, they are not transferred elsewhere: when they cease to exist in the healthy soul, they cannot exist anywhere else. (Augustine, Enchiridion, 11)

The payoff of this

consideration is obvious. The problem from evil treats evil as a thing, as having

a reality of its own. Evil, then, provides no basis for denying the existence

of God.

Is this too quick? Does

this get God off the hook, so to speak?

One might respond that God,

being all good, would have made things better, not lacking any of the things

that they lack.

What might be said here?

The "We know that God exists" response

If I know that a

proposition is true, then I know that the claim that it is impossible or

unlikely is false and that arguments to this effect are unsound. I know that

‘God exists’ is true; therefore, I know that the claim ‘God does not (or cannot

or likely does not) exist’ is false, as are claims that imply this. The reasons

I have for believing ‘God exists’ must be addressed.

The argument does not account for the reasons people have… arguments for the existence of God.

(We'll be looking at some of these next time.)

Classical theism and the

free will defense

According to Aquinas and

other classical theists, God did not start the world and step away. The world

and all that happens in it is radically dependent on God for its being at every

moment.

Creation is a continuous

act. Everything has God as its first cause, even human choices.

What does this mean for the

free will defense?

God gives genuine agency to

created things. Some cause what they cause necessarily, others contingently.

But, in an important sense, what is caused contingently is also necessitated.

God’s will does not fail.

God chooses to cause some effects by deficient causes. And, so, such are

contingent in the order of secondary causation but necessary in the order of

primary causation.

(This primary-secondary

cause distinction is a difficult one to grasp.)

What can be said about

human freedom? Freedom of a certain kind is necessary for moral responsibility.

This freedom is the power of authorship. One’s choice cannot be necessitated.

Nor, is it enough that it is not necessitated. It must be up to the person.

St. Thomas believes that

this up-toness is safeguarded by the order of secondary causation. God's

causation of our choices and actions is not interference. It does not undermine

our freedom.

Philosophy of Religion Class 5:

Plantinga’s Free Will Defense and Rowe’s Problem

of Evil

Plantinga’s Free Will Defense

Mackie’s argument…

The following are

inconsistent (cannot all be true):

1.

God is omnipotent.

2.

God is wholly good.

3.

Some evil exists.

To see this, we must add some

further principles.

4.

If something is wholly good, it always eliminates

as much evil as it can.

5.

If something is omnipotent, it can do anything.

Plantinga on (4):

Premise (4) is not necessarily

true. There might be evils which cannot be eliminated without thereby

eliminating outweighing goods. It is possible that eliminating all evil

would involve eliminating outweighing goods.

One such good might be human

freedom…

Aquinas: ST. 1.2.3

Reply Obj. 1: As Augustine says

(Enchiridion xi): Since God is the highest good, He would not allow any evil to

exist in His works, unless His omnipotence and goodness were such as to bring

good even out of evil. This is part of the infinite goodness of God, that He

should allow evil to exist, and out of it produce good.

Plantinga’s free will defense

Mackie anticipates a free will response…

God could have and so would have

made men who choose freely what is good in all cases.

God could have and so would have

made a world in which men choose freely what is good in all cases.

(It is not implausible to me that a world in which people sometimes

choose evil might be a better world by virtue of an outweighing good or goods.)

Plantinga rejects Mackie’s suggestion.

He begins by arguing that there are possible worlds involving

free choices that God cannot actualize (make actual, create).

(This corresponds to a rejection of Mackie’s 5th

premise.)

Suppose that Tom

rejects an offer of $500.

Would he have freely accepted an

offer of $600?

If yes, then God could not have

actualized any relevantly similar world in which Tom freely rejects an offer of

$600.

Why not? This would contradict his

freedom—an impossibility.

It is possible, he argues, that a world in which there are creatures

who make morally significant choices and never sin is one that God could not actualize.

Why could God not have created a

world containing only those who could act wrongly but always choose to act

rightly?

God can create people who choose

freely, but it’s up to them how they use their freedom, and it may be that in

all worlds in which people make morally significant choices, people at least sometimes

sin.

Therefore, it may be that a world

in which persons make morally significant choices and never sin is one that God

could not actualize.

So, Mackie’s conclusion is

false. There’s no contradiction.

Objections

Plantinga’s objection depends on

the idea that claims about hypothetical free choices have truth values. It is

not at all obvious that claims such as those regarding hypothetical free choices

are true or false. What might make them true? Neither God’s will nor the

hypothetical choosers.

The classical theist will reject

the idea that God operates in the same manner as his creatures… contemplating

possibilities etc.

Rowe’s evidential argument from evil

1.

There exist instances of intense suffering / which

an omnipotent, omniscient being could have prevented without thereby losing

some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse.

2.

An omniscient, wholly good being would prevent the

occurrence of any intense suffering it could, unless it could not do so without

thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse.

3.

Therefore, there is no omnipotent, wholly good

being.

The first part of premise one is the evidential part. The second

part is not, and it is precisely this fact that drives a prominent objection to

the argument.

Why does he believe the second part is true? Because it seems

to be the case.

He does not think this is conclusive but provides a

cumulative argument to the effect that there are enough instances of intense

suffering that appear to lack this purpose to render highly probable the claim

that they lack this purpose.

In defense of premise 2, Rowe suggests that this “accords

with our basic moral principles” and so cannot be rejected by anyone.

This assumes theistic personalism… and the idea that God is a

moral agent in the same sense as we are, governed by the same moral principles.